As the nationwide Optus outage that left millions of Australians with no service is investigated, the repercussions are being felt strongly within the company. Paul Budde reports.

ON THE DAY of the Optus network outage, I wrote an article with my initial assessment. I fine-tuned it the following week and also used it for my submission to the Senate Inquiry into the Optus network outage.

The outage on Wednesday 8 November sent shockwaves across the nation, prompting a deep dive into the incident’s root causes, impact and the company’s response. I closely monitored the developments as they evolved and engaged in numerous media interviews to shed light on the situation.

In collaboration with global colleagues, I provided a comprehensive analysis that delves into the complexities of the event, highlights potential industry-wide solutions and emphasises the critical need for resilience and continuous improvement in the face of such disruptions.

As we navigate the aftermath of the Optus network outage, the submission serves as a catalyst for a broader conversation on industry resilience, emergency response strategies and the imperative for continuous improvement. The incident underscores the interconnectedness of our digital infrastructure and the need for proactive measures to mitigate the impact of unforeseen disruptions.

In a rapidly evolving technological landscape, learning from such incidents is not just a necessity but a responsibility to fortify the foundations of our digital connectivity.

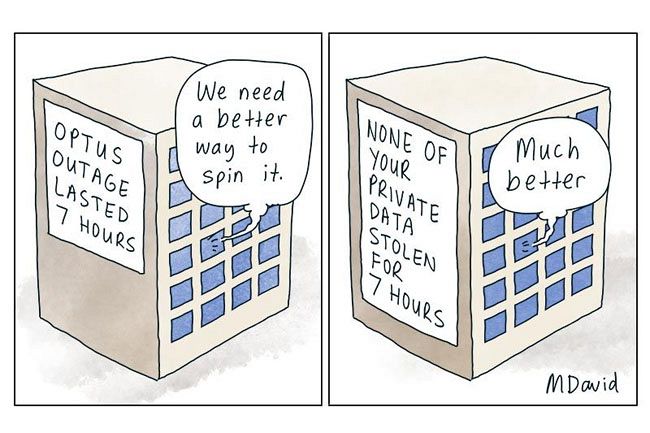

There was also a widespread condemnation of Optus’s poor handling of the situation, which inevitably led to the resignation of Optus’s CEO, Kelly Bayer Rosmarin. To the outside world, at least, it looked like the company didn’t have a proper disaster plan and it seemed like the company found it hard to take full responsibility, pointing in an ambiguous way to “others” who might need to share in the blame.

This, in particular, didn’t sit well with me in relation to some of the comments or insinuations made by Bayer Rosmarin. It was not the actual technical outage that made it difficult to maintain her position. She clearly was unable to show proper leadership under the pressure of this disaster and apparently, the September 2022 hacking scandal had not provided her with the essential disaster management lessons that we all had expected.

This started to happen when she pointed to the problems occurring as a result of a problematic software upgrade coming from another company with whom Optus is internationally connected (this is called peering). These companies are the parent company Singtel in Singapore, China Telecom, the U.S.-headquartered global content delivery network Akamai, and Global Cloud Xchange, owned by Jersey-based 3i Infrastructure and formerly known as Flag Telecom.

The ambiguity of that message, of course, triggered reactions. Could it be China Telecom? We all understand the geopolitical fallout if that indeed was the case. Akamai immediately reacted and said it was not them, obviously worried about its reputation. So, Optus had to come clean on this and then pointed to its own parent, Singtel, as being the company that had updated its software – most likely with an error in the software – which triggered the outage.

Singtel furiously reacted to this, indicating it was Optus’s responsibility to properly manage its own network. Again, it looked like Optus didn’t want to take full responsibility. The reality, however, is that it is in control of what enters and doesn’t enter its network.

Errors are not uncommon. Outside information gets checked before it is allowed to enter the other network. This is done through filters and settings within the equipment (routers) of the network operator, allowing for the management of communication between networks. This should have filtered out bad software codes, which most of the time happen through human errors in the coding.

Next, Optus mentioned that the company had used all the specified settings as recommended by its router supplier, Cisco, again trying to shift blame and still not taking full responsibility. In the end, it is again the responsibility of Optus to set the filters and settings based on its requirements that are specific to its network operations.

Again, another insinuation regarding the 000 calls. The CEO mentioned that this is a separate network.

Bayer Rosmarin’s words at the Senate Inquiry on November 17 were:

“We don’t run the triple-0 system; we participate in the triple-0 system.”

As I have never heard of a 000 failure in previous outages, it looks like the 000 network is pretty robust. But future investigations will tell.

While this has been a very serious event that nobody within the company saw coming, the way it has been handled by the company is an example of how not to do it. So, hopefully, this time Optus will learn from it, as I am sure will the rest of the industry.

Paul Budde is an IA columnist and managing director of independent telecommunications research and consultancy organisation, Paul Budde Consulting. Follow Paul on Twitter @PaulBudde.

Related Articles

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.